Trust

“We always hear that Black men are hard to reach with health care messages. But the truth is we’re not hard to reach. You just have come to us where we are.” -Marcus Murray, MPH

By Christine Wilson

For our most recent Policy Consortium, “Learning from Communities,” we were looking for something different. Instead of having researchers talk about the work they do in communities, we wanted the community leaders and the researchers to talk with each other, have an actual conversation. The emphasis was more on the relationships– why they worked, how they met the needs of the communities–than on data or even outcomes.

We asked a range of people we know are doing this kind of work together, Alma McCormick and Suzanne Held with their “sacred partnership” that is increasing cancer awareness and prevention in the Crow Nation, Silvia Amesty using PhotoVoice with sex workers in the Dominican Republic, Stacy Van Gorp and Melanie Lawrence developing tools to promote better communication for CF patients and their health care providers, Jim Chaliak and Katie Cuevera improving health with indigenous populations in Alaska.

In a nutshell or two, what did we hear? Here are just a few of the many lessons. That in the Crow Nation, people use stories to communicate what is important to them, and that those stories cannot be broken down or carved into “themes.” They are whole. That you can learn an enormous amount by giving people a camera and asking them to take images of something that matters to them, and then explain why. That even people who endure enormous discrimination and often live difficult, painful existences can find joy and resilience in their lives. That you can build an effective tool using a series of stock photographs to help patients and doctors talk about what they want from their relationships. That a young Black man cannot rely just on his academic credentials to work with his community. He has to build trust by being there, listening, paying his dues. That in indigenous communities, the words and support of the elders is essential to being welcomed into that town.

What came through so strongly in all of these conversations was these are genuine relationships, built on mutual respect and trust, and that those relationships take time, often years to build. Okay, most good relationships do need time, but the old paradigm for community research has been much more one in which the researchers came in with an agenda, a list of deliverables and a time table. That’s basically how most research works. Investigator decides what she wants to study, gets funding for a specific period of time, recruits participants, does the study, analyzes the results and moves on. The assumption, often very well intended, is that the community benefits from this knowledge. But for many communities, that doesn’t work anymore.

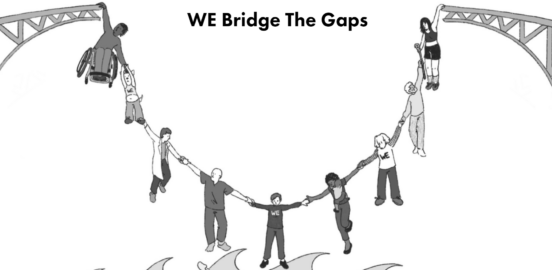

Communities don’t want outsiders to tell them what to do or what they need. They are tired of people showing up, doing their study and then leaving. Communities are experts about themselves and their people. They know what they need, what will work and what will not, and they want to be part of the process of planning, implementing and evaluating every project. They want to work with people who take the time to get to know them, to listen, not to make assumptions, to let them speak for themselves. As Karriem Watson pointed out, the academic world has much to learn from the community and one of the key jobs for any researcher is to be able to live in both worlds, to speak both languages, to bridge the gaps that always separate them.

To succeed, community based research must have people from that community at its center. But, that doesn’t mean that “outsiders” can’t be effective community researchers. Our conversations were clear demonstrations that these partnerships not only exist, but thrive when researchers bring open minds and hearts to their work, learn as well as teach, and most of all take the time to establish and nurture relationships.

Trust

Caregiving, Health Literacy, Needs Navigation, Trust

Caregiving, Storytelling, Trust

Equity, Policy Consortium