Register for Policy Consortium

By Christine Wilson

Take a few seconds and think of some of the iconic photos that seem to crystallize moments. The naked Vietnamese girl running from her napalmed village. The anguished young woman kneeling over the body of the student gunned down by the National Guard at Kent State. Dorothea’s Langes portrait of the “Migrant Mother,” from the Great Depression.

They, and so many more, are images that capture something essential, that we never forget, maybe even change our lives. As powerful as they are, they all have something in common. They were taken by outsiders, photojournalists who recorded what they saw, but did not directly experience it.

Recently, Gwen Darien and I journeyed with Ed Cunicelli, a photographer and videographer, to shoot a “documentary” with Silvia Cunto-Amesty and a Columbia medical student/soon-to-be-resident in internal medicine, Alani Estrella, on the work they are doing using an approach called Photovoice with a number of communities. These include Venezuelan women who immigrated to the Dominican Republic and have been forced to become sex workers, HIV patients in New York and medical students whose lives, education and sense of community were disrupted by COVID.

Photovoice began in the United Kingdom as a means of doing “ethical photography for social change.” It involves providing members of diverse communities with cameras, teaching them how to use them and asking each one to record something about their own experience or their community that helps to tell their story. The results are startling, evocative, extraordinary, unexpected and beautiful.

When I asked Dr. Amnesty why taking pictures is so powerful, she said, “Even the best photojournalists are seeing something and interpreting from their own perspective. When people choose their own images, their own subjects they are reflecting their own lived experiences both as individuals and members of their communities. It’s different.”

At the moment she said this, Ed was recording it. He is a man with a strong social conscience who has done remarkable shoots with a wide range of people and communities, ranging from children’s hospitals to Native American reservations to rural health centers. He doesn’t just take photos, he cares about the stories and the people that lie behind them. He listens. He respects. He observes closely. So, how did he feel about Dr. Amnesty’s comment? “I have to agree with her,” he said. “As much as I try to understand a community and its people, to reflect that essence, I am still not one of them.”

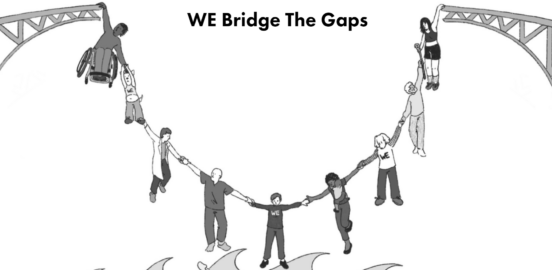

At our upcoming Policy Consortium, we will highlight Dr. Amesty’s work both in the documentary and her Keynote Address, Finding Community Through Images. The event will also feature speakers who are participating in community-based research which seeks to work with and learn from communities. The full agenda is on the event site, linked below.

Trust

Caregiving, Health Literacy, Needs Navigation, Trust

Caregiving, Storytelling, Trust

Equity, Policy Consortium